Designing for Safety and Reliability in Multicore Hard-Real Time Applications

June 03, 2025

Blog

Hard real-time applications, including automotive, avionics, industrial, and military systems, demand deterministic execution times for mission-critical tasks. To increase performance, many of these applications utilize multicore processors to split complex software code across many cores to reduce overall processing execution time.

While this tends to lower the average execution time for a given set of tasks compared to single-core processor-based systems, contention between cores for hardware shared resources (HSR) introduces variability. This variability results in a wider spread between the best-case execution time (BCET) and worst-case execution time (WCET).

WCET is a crucial factor in designing reliable and safe hard real-time systems that need to guarantee that mission-critical tasks are completed within a set time window. If such a task takes too long to complete, a crucial function of the system may fail. For example, consider if important data is not read from a sensor or bus on time. Every subsequent function could be processing with old or bad data, leading to undesirable results. In the case of an airplane or vehicle, missing mission-critical timing deadlines could be catastrophic.

This article will explore the process of designing systems that safely and reliably meet hard real-time timing requirements, including understanding industry standard guidance documents, how execution time can be negatively impacted by multicore processor architectures, and ways to determine the WCET of a mission-critical task so developers can guarantee timing deadlines are met every time.

Industry Standard Guidance Documents

To address execution timing challenges in multicore processor-based systems, embedded software developers can turn to guidance documents like CAST-32A, AMC 20-193, and AC 20-193, depending upon the application and industry. For example, CAST-32A from the Certification Authorities Software Team (CAST) outlines important considerations for multicore processor timing and sets Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) objectives for a better understanding of the behavior of a multicore system. In Europe, the AMC 20-193 document has superseded and replaced CAST-32A, and in the U.S., the AC 20-193 document has done the same. These successor documents, collectively referred to as A(M)C 20-193, largely duplicate the principles outlined in CAST-32A.

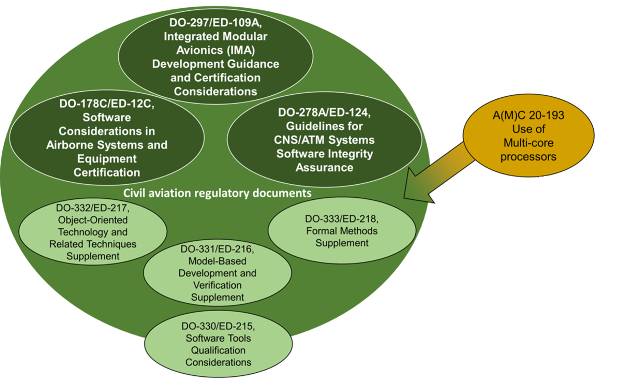

Figure 1: Guidance documents like A(M)C 20-193 support developers of hard real-time systems to address multicore processing issues and meet the strict timing requirements of industry regulations and standards. (Source: LDRA)

Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the relationships among key civil aviation documents, outlining the landscape of guidance available to developers. Guidance documents like A(M)C 20-193 describe acceptable means for showing compliance with industry reliability specifications for aspects related to multicore-based systems. In this example, A(M)C 20-193 places significant focus on developers providing evidence that the allocated resources of a system are sufficient to allow for worst-case execution times. Such evidence requires that developers adapt development processes and tools to iteratively collect and analyze execution times in controlled ways that help them to optimize code throughout the development lifecycle.

Specifically, A(M)C 20-193 specifies multicore processor timing and interference objectives for software planning through to verification that include the following:

- Documentation of multicore processor (MCP) configuration settings throughout the project lifecycle, as the nature of software development and testing makes it likely that configurations will change. (MCP_Resource_Usage_1)

- Identification of and mitigation strategies for MCP interference channels to reduce the likelihood of runtime issues. (MCP_Resource_Usage_3)

- Ensure that MCP tasks have sufficient time to complete execution and adequate resources are allocated when hosted in the final deployed configuration. (MCP_Software_1 and MCP_Resource_Usage_4)

- Exercising data and control coupling among software components during testing to demonstrate that their impacts are restricted to those intended by the design. (MCP_Software_2)

A(M)C 20-193 covers partitioning in time and space, enabling developers to determine WCETs and verify applications separately if they have verified that the multicore-based system itself supports robust resource and time partitioning. Making use of these partitioning methods helps developers to mitigate multicore contention issues. Note that not all hardware shared resources can be partitioned in this way. In either case, the specifics of DO-178C require evidence of adequate resourcing.

It's important to note that these are guidance documents and are not prescriptive requirements, and compliance may not even be mandatory, depending on the industry. Rather, they guide and support developers toward adhering to widely accepted standards like DO-178C. A(M)C 20-193, for example, does not specify exact methods for achieving objectives, leaving developers to implement measurements in ways that best suit their application and development environment. Alternative means of compliance may be used but must still meet the relevant requirements, ensure an equivalent level of safety, and be approved by the appropriate agencies or governing bodies.

Worst-Case Execution Time

To be able to assure that enough processor resources are allocated to guarantee the reliable execution of mission-critical tasks, developers must determine the worst-case execution time (WCET) for each task. Note that not every timing deadline is mission-critical. Nothing catastrophic occurs if an update to a display is delayed by a few milliseconds. Thus, the first step in determining WCET is to assess which tasks are hard real-time and critical to reliable operation.

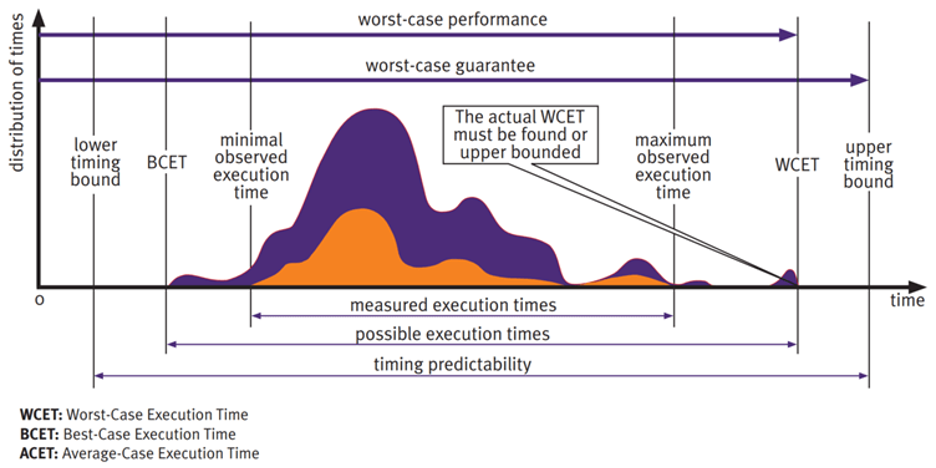

Figure 2: Measured execution times (orange) are but a subset of the possible execution times (purple). To ensure that the worst-case execution time (WCET) can be met, developers use the measured execution times to estimate the WCET. To assure safe and reliable execution, developers can choose an upper timing bound that guarantees the actual WCET will be met.

Figure 2 shows execution times for a particular mission-critical task. The upper curve in the diagram depicts the set of all possible execution times and their distribution, which will vary naturally. Calculation of the WCET must consider all possible inputs and dependencies, including specification violations. The more contention there is among tasks, the greater the potential variability, leading to a higher WCET.

For a single-core processor, upper and lower timing bounds for a task can be reasonably approximated by computing timing bounds for different paths in the task and searching for the overall path with the longest execution time. To maintain upper timing bounds, sufficient CPU capacity can then be allocated and maintained.

Assessing WCET in a multicore processor is typically far more complex than for a single-core processor because of the increased variability when using a multicore architecture based on how the cores interact with each other. Contention for the use of a hardware shared resource (HSR), such as a peripheral or memory, can add delay to execution time. For example, consider two cores that need to access a variable in shared memory. While one core reads and modifies the variable, the variable must be locked out from the other core. This prevents the second core from modifying the variable while the first core is using it. While this protects data integrity, it introduces a potential processing delay for the second core as it must wait for the variable to be released by the first core. The more contention between cores, the greater the delay and the greater the impact on execution time.

Determining WCET in a multicore environment is a more complex calculation because the contention between cores is dynamic and changes based on the particular combination of tasks running concurrently. In simple terms, the WCET is the execution time for the combination of tasks across cores that produces the most overall delays. However, uncovering this particular combination may not be feasible, given the innumerable combinations possible. For example, testing and measurement of the system will only yield a subset of the possible execution times (see the orange section in Figure 1), compared to the full set of possible execution times (see the purple section in Figure 1).

Further complicating WCET calculations is that contention for hardware shared resources is largely unpredictable, disrupting the measurement of task timing. For example, while multicore processors often have private L1 caches, consider the variability that can arise from contention for shared L2 and L3 caches. Simulating the extreme circumstances that could lead to significant delays from such contention is not realistic using static approximation methods. Instead, to generate usable WCET measurements, developers must rely on measurements from iterative testing to gain as much confidence as possible in understanding the real-world timing characteristics of mission-critical tasks.

Given the complexity of analyzing the dynamic variability of execution time, it can be difficult to definitively calculate the upper timing bound on WCET. In other words, the worst-case observed execution time will likely be short of the actual possible worst-case execution time. Thus, to guarantee reliable and safe performance, developers use the measured WCET to estimate a worst-case guarantee upper timing bound. This upper timing bound is based on extensive WCET analysis to ensure that the system will be able to execute deterministically under all environmental conditions.

Analyzing Multicore WCET

As recognized by industry guidance documents and standards, developers can employ various techniques for measuring execution timing in complex, multicore processor-based systems. Three proven methods that can provide valuable timing data throughout the development cycle include 1) Halstead’s metrics and static analysis (early-stage development), 2) empirical dynamic analysis of execution times (mid-stage), and 3) analysis of application control and data coupling (late-stage).

Early-Stage Development - Halstead’s Metrics and Static Analysis: Halstead’s complexity metrics can act as an early warning system for developers. This approach provides insights into the complexity and resource demands of specific sections of code. By employing static analysis, developers can use Halstead data with real-time measurements from the target system. This helps developers ensure a more efficient path to lower the WCET.

Such metrics and others shed light on timing-related aspects of code, including module size, control flow structures, and data flow. By identifying code sections of larger size, higher complexity, and more intricate data flow patterns, developers can prioritize their efforts and fine-tune code that puts the highest demands on processing time. Optimizing these resource-intensive areas early in the lifecycle is an effective way to reduce the risk of timing violations and simply later analysis processes.

Mid-Stage Development - Empirical Dynamic Analysis of Execution Times: When modules fail to meet timing requirements, developers can measure, analyze, and track individual task execution times to help identify and mitigate timing issues (empirical analysis). As it is critical to eliminate the influence of configuration differences between development and production, such as compiler options, linker options, and hardware features, analysis must occur in the actual environment where the application will run. Thus, empirical analysis cannot be fully employed until a test system is in place.

To account for environmental and application variability between runs, sufficient tests must be executed repeatedly to ensure accurate, reliable, and consistent results (empirical dynamic analysis). To be able to execute sufficient tests within a reasonable timeframe, automation is essential. Automation also reduces developer workloads as well as eliminates human error that can occur during manual processes.

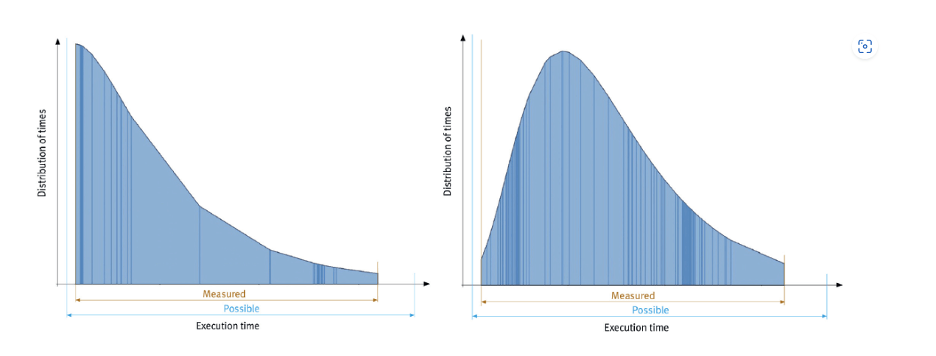

Figure 3: Execution time histograms from the LDRA tool suite. (Source: LDRA)

Figure 3 shows an example of empirical dynamic analysis using the LDRA tool suite. Modules are fitted with a “wrapper” test harness on the target device to automate timing measurements. Developers can define specific components under test at the function level within a subsystem or as part of the overall system. Additionally, CPU stress tests, such as using the open-source Stress‑ng workload generator, can be specified to further improve confidence in the analysis results.

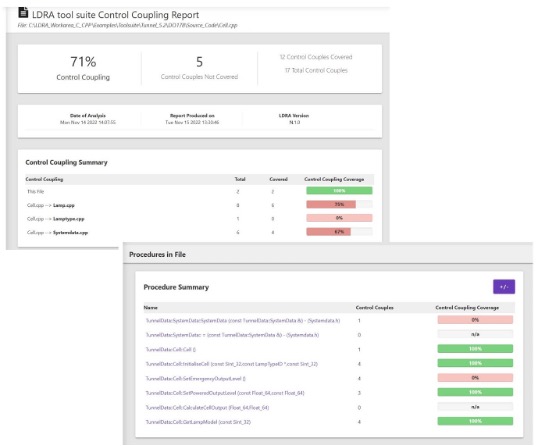

Late-Stage Development - Application Control and Data Coupling Analysis: Evaluating contention involves identifying task dependencies within applications, both from a control and data perspective. Using control and data coupling analysis, developers can explore how execution and data dependencies between tasks affect each another. The standards insist on such analyses not only to ensure that all couples have been exercised, but also because of their capacity to reveal potential problems.

The LDRA tool suite provides robust support for control and data coupling analyses. As shown in Figure 4, control and data coupling analyses can help developers identify critical sections of code requiring optimization or restructuring to improve their timing predictability and overall resource utilization.

Figure 4: Data coupling and control coupling analysis reports from the LDRA tool suite. (Source: LDRA)

Performance is often thought of in terms of the average execution time. For mission-critical tasks, the WCET is the limiting factor impacting system reliability. The WCET of a task is an important outlier as it impacts a system’s ultimate reliability. Following industry guidance documents and standards, developers can evaluate a system’s WCET using a variety of approaches and tools. In this way, they can accurately determine a sufficient upper timing bound that guarantees all of a system’s hard real-time requirements are met under all operating conditions.

Jay Thomas, technical development manager for LDRA, has worked on embedded controls simulation, processor simulation, mission- and safety-critical flight software, and communications applications in the aerospace industry. His focus on embedded verification implementation ensures that LDRA clients in aerospace, medical, and industrial sectors are well grounded in safety, mission, and security-critical processes.