Engineering Real-Time: Lessons Learned While Chasing Determinism, Part 2

November 25, 2025

Blog

In Part 1 of this series, we talked about two key real-time scheduling algorithms — Earliest Deadline First (EDF) and Priority Inheritance (PI) — and how they tie into our real-time database management goals. Those algorithms decide when each transaction should run, but that’s only the beginning.

To make them really work in practice, we also need solid timing measurements and built-in runtime monitoring inside the database kernel. Part 2 takes that next step — making sure the database kernel not only follows the schedule but actually meets every deadline, every time. We’ll look at how timing is measured, monitored, and verified, and how the same approach can be used in other hard real-time middleware to make sure that “on time” really means on time.

How We Know When “On Time” Is Actually On Time

All of that starts with a simple but fundamental question: how do we measure time accurately inside a real-time database?

Every RTOS provides its own timer facilities, but they all have trade-offs. The regular system tick is cheap but not precise. High-resolution timers give micro- or nanosecond accuracy, but they cost more CPU cycles. One-shot timers can act as deadline guards, but they’re not practical for continuous monitoring. The solution was to make the timing base configurable up front. The database kernel can use a coarse or fine time source depending on the target hardware, with calibration constants defined once at build time. This way, every transaction runs with a known, measurable time budget. Implementing this requires selecting an appropriate timing source exposed by the platform. Examples include clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC) in POSIX systems, xTaskGetTickCount() in FreeRTOS, k_uptime_get() in ZephyrOS, as well as CPU-specific mechanisms for obtaining the processor’s cycle count, such as the rdtsc instruction on x86 or the CNTVCT/PMCCNTR registers on ARM architectures.

With time measurements in place, the next step is determining the rollback scope if a transaction must be stopped. Most database systems can’t really answer that; rollback time tends to be unpredictable. Hard real-time database kernels can’t operate that way; the time required to rollback a transaction must be known. Therefore, the kernel uses a copy-on-write (COW)–based transaction mechanism built on a page-organized storage layout, so it always knows which pages were modified and how long it takes to restore them. That lets the kernel calculate the total rollback cost in advance. In other words, time isn’t guessed — it’s accounted for.

It’s also worth noting that these measurements are possible even for persistent databases stored on flash memory devices. Without taking explicit measures, flash I/O is less predictable than RAM access because of erase–program cycles, wear-leveling needs, and various background housekeeping tasks inside the flash controller. But when the database kernel controls flash management, it can track the Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET). And because the amount of data written during rollback is small, page-bounded, and tracked dynamically at runtime, the rollback duration remains measurable and predictable.

With rollback costs accounted for, the next question is when to actually perform the timing checks. Continuous polling would be wasteful, and random checks would be unsafe. The answer is verification points (VPs) — small, predictable places in the database kernel where the internals are in a consistent state and the system can safely interrupt a transaction if needed. These points are placed statically in the code: before and after page locks, around flash I/O, and inside long loops that shouldn’t run unchecked. Each one is a controlled checkpoint where the database can ask, “Do I still have enough time left?”

By default, a verification point simply reads the system clock and compares it to the transaction’s deadline. But applications can provide a custom callback instead and run whatever timing logic they prefer. Common examples include arming a timer for a specific duration and using its signal to request an abort or feeding a hardware watchdog to indicate that the system is still alive.

These verification points also enable safe transaction preemption. Instead of cutting a transaction off mid-operation, the kernel can stop it cleanly at one of these verification points, roll back the bounded amount of work, and release control to the scheduler. That’s how we keep timing predictable without compromising consistency.

There’s No Real-Time Without Profiling

The third challenge is harder and less obvious: budgeting for various lags — the time between the moment the database kernel decides to stop the transaction and the moment control actually returns to the application. There’s always a tiny window between the “abort now” decision and the completion of rollback. That lag depends on two factors:

The third challenge is harder and less obvious: budgeting for various lags — the time between the moment the database kernel decides to stop the transaction and the moment control actually returns to the application. There’s always a tiny window between the “abort now” decision and the completion of rollback. That lag depends on two factors:

1. The number of instructions between verification points — the horizontal lag. The kernel measures these delays during testing and runtime monitoring, then uses the collected data to size its safety margin. Over time, the system learns the worst-case lag between verification points and incorporates that number into its scheduling calculations. That’s how “abort in time” becomes just as predictable as “finish in time.”

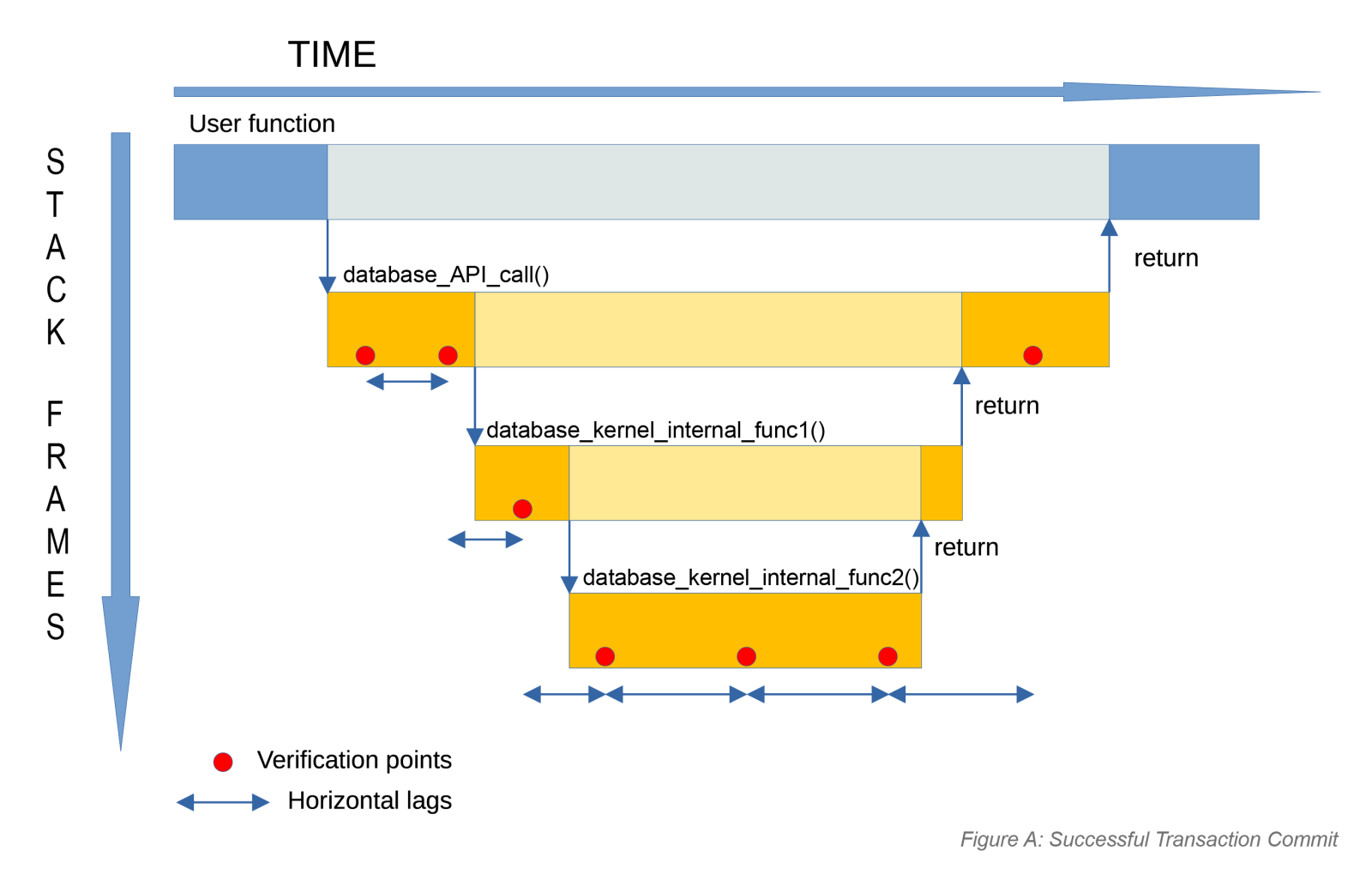

2. The number of instructions executed when returning from nested calls — the vertical lag. To minimize this delay, the database kernel uses standard C library function longjmp() to quickly unwind the stack back to a known state. Before that jump, a chain of cleanup callbacks run to release locks, restore internal structures, and bring the system back to a consistent state.

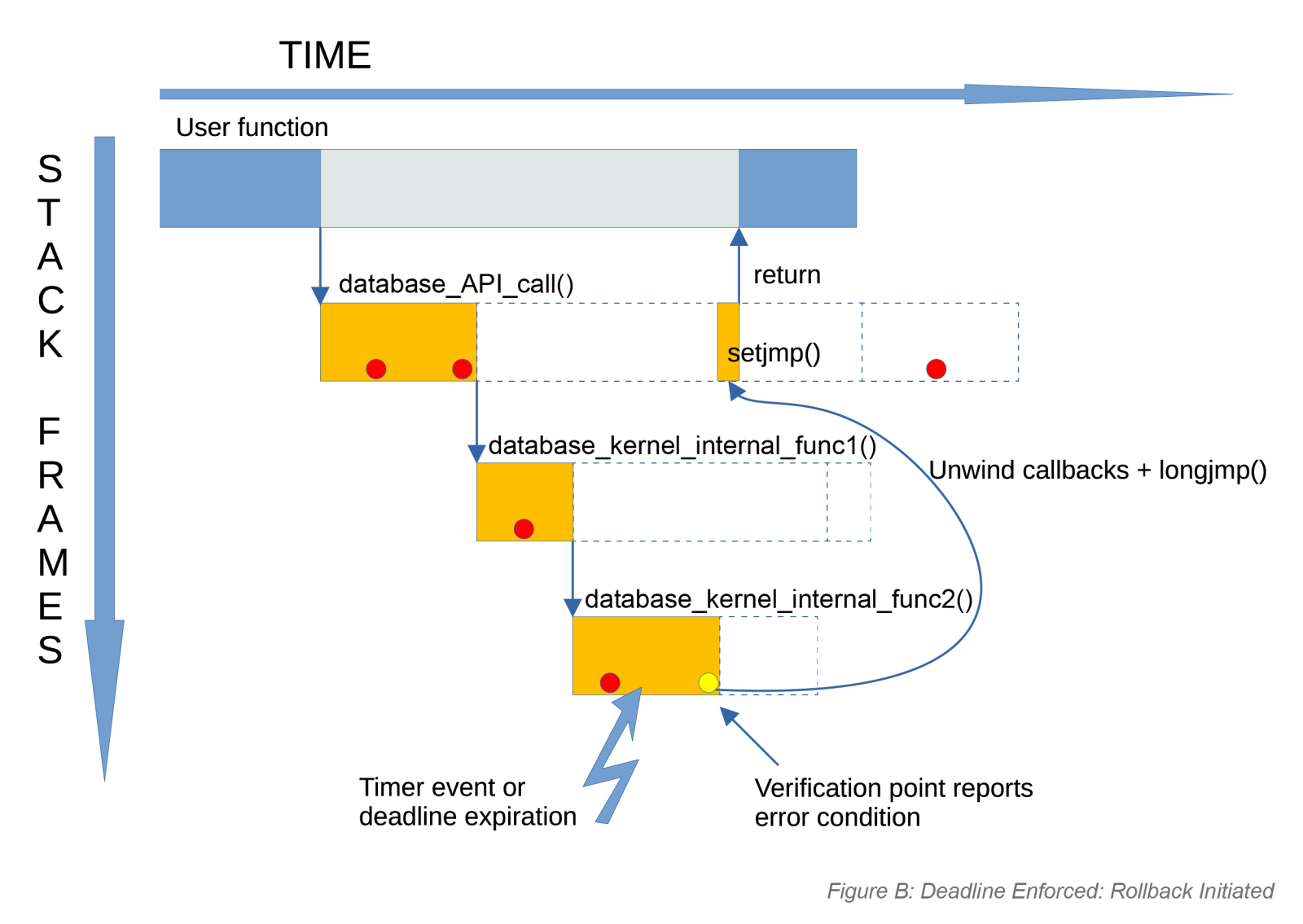

The diagrams show the lags during normal execution and when a deadline fires. In the Figure A diagram, the application calls a database API function, which calls internal functions. Verification points are reached, but none trigger, so execution finishes normally. The only lag is the natural return-chain unwind. In the Figure B diagram, the deadline expires. The nearest verification point detects it and triggers longjmp(). This eliminates the return-chain lag: the stack is popped instantly, and control jumps straight back to the application.

Applications must account for these lags when choosing deadline timeouts. Because verification points are placed statically in the kernel and the work between them varies across platforms, predicting the lag in advance is nearly impossible, so profiling is the only reliable method. In practice, developers measure how long it takes for control to return from the database API after a triggered deadline on the actual hardware/software setup and fold that value into the application’s own deadlines.

Applications must account for these lags when choosing deadline timeouts. Because verification points are placed statically in the kernel and the work between them varies across platforms, predicting the lag in advance is nearly impossible, so profiling is the only reliable method. In practice, developers measure how long it takes for control to return from the database API after a triggered deadline on the actual hardware/software setup and fold that value into the application’s own deadlines.

When a Transaction Stops: Error Handling

And that brings us to the topic of the next installment in this series: error handling. Once timing and verification are in place, the next step is deciding what happens after an enforced abort — how the system reports it, how consistency is maintained, and how applications recover gracefully without losing control of the timeline.