Engineering Real-Time: Lessons Learned While Chasing Determinism Part 4

December 11, 2025

Story

In Part 1 and Part 2, we looked at how EDF and PI scheduling support real-time database behavior, and why true timing guarantees also depend on precise measurement, predictable rollback, well-placed verification points, and profiling on real hardware.

Part 3 then examined what happens when a deadline is actually enforced: the failure path has to be just as deterministic as the commit path, and deep call stacks combined with flash I/O make traditional return-based unwinding unpredictable. To keep control, the kernel uses a single, bounded escape route (setjmp/longjmp) to restore database consistency. This next section turns to a new question: how real-time guarantees can be extended all the way down to persistent storage — specifically, flash memory.

Persistence in Real-Time Systems: All Roads Lead to NAND

In modern data-driven hard real-time systems, real persistence is often necessary, and RAM can’t do that — it’s small, volatile, and not scalable in embedded gear. HDDs barely deserve a mention; nobody building real-time hardware would tolerate their size or power draw anymore. FRAM tops out around 8 MB and isn’t really a mass-market option anyway — the density is low and the cost per megabyte is often prohibitive. Other NVRAM parts sit in the same 1–8 MB range, with only a few rare 32–64 MB modules out there, and those tend to draw too much power and cost far too much. That basically leaves NAND flash: high-density, low-power, compact, inexpensive, and already a de-facto reality in today’s embedded hardware. In practice, it’s the only persistent medium that can store the volumes these systems generate without blowing up the size, cost, or power budget, which is why NAND flash ends up being the practical choice.

Making Flash Predictable: The Trouble With Black-Box FTLs

Much has been written about software support for flash memory — the erase-before-write rule, block remapping, wear leveling, bad-block management, ECC, garbage collection, write amplification, and all the supporting logic needed to keep raw flash usable. In most systems, all of this is hidden behind a Flash Translation Layer (FTL), which masks these details and presents a single, consistent storage interface to the rest of the stack. What gets far less attention is the predictability angle: how a higher-level component, in our case, a real-time database kernel, can guarantee bounded worst-case latency when the FTL runs housekeeping, triggers long erase cycles, moves data around, or stalls on its own internal housekeeping.

There are two sides to predictable transaction timing when persistent storage is involved. The first we touched on earlier: the kernel must know how much data it needs to write, and CoW-based transaction algorithms handle that.

The second is less algorithmic — the kernel needs direct control over media access and a clear idea of what an I/O call will cost right now. With a standalone FTL in the path, that visibility disappears. The FTL becomes a black box focused on flash longevity, running flash management code whenever it decides to, and those operations can introduce latencies that are both uninterruptible and unpredictable. At first glance, the fix seems obvious: integrate the FTL into the database kernel. In practice, that integration is anything but straightforward. Flash management involves device-specific program/erase characteristics, variable latency profiles, block-allocation policies, wear-leveling strategies, and vendor-specific error-handling mechanisms that differ from chip to chip. Maintaining deterministic behavior across all of that is a nontrivial engineering problem. Even so, from the real-time guarantees standpoint, we found no viable alternative: the only practical approach was to eliminate the opaque layer and bring the essential FTL functionality directly into the database kernel.

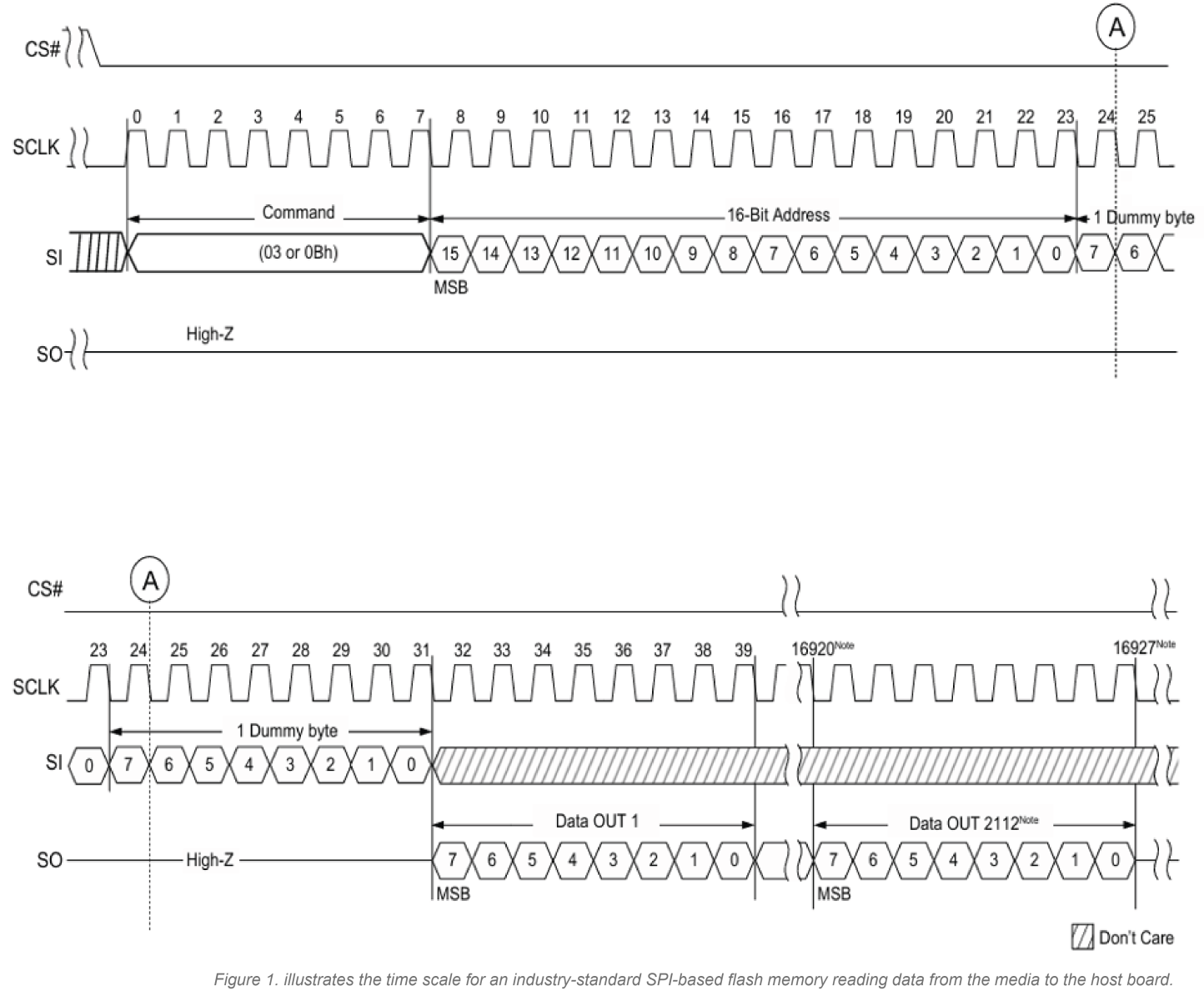

The next question is how deterministic access is actually achieved. Flash cells operate on well-defined electrical properties, and their read, program, and erase latencies are set by the chip’s internal design, with variations that remain within the bounds specified in the datasheet. Manufacturers publish precise timing parameters, and these intrinsic operation times stay stable across interface types because the interface affects transfer bandwidth, not the underlying cell operations (see Figure 1).

Serial (SPI) NAND is common in simpler hardware designs due to its low pin count, while parallel NAND is used in higher-capacity systems where throughput is critical. Parallel devices often follow the ONFI (Open NAND Flash Interface) standard, which defines the command set, timing rules, and electrical behavior. ONFI standardization allows a single low-level driver to support a broad range of NAND devices while still requiring device-specific configuration based on each chip’s parameter page and enabling vendor-specific extensions such as OTP regions, unique identifiers, or additional command capabilities. With the physical foundation established, the next step is to look at what the FTL actually does.

Serial (SPI) NAND is common in simpler hardware designs due to its low pin count, while parallel NAND is used in higher-capacity systems where throughput is critical. Parallel devices often follow the ONFI (Open NAND Flash Interface) standard, which defines the command set, timing rules, and electrical behavior. ONFI standardization allows a single low-level driver to support a broad range of NAND devices while still requiring device-specific configuration based on each chip’s parameter page and enabling vendor-specific extensions such as OTP regions, unique identifiers, or additional command capabilities. With the physical foundation established, the next step is to look at what the FTL actually does.

The core FTL job is mapping the logical pages the host sees to the physical pages on the flash, using translation algorithms, wear leveling, and bad-block management to deal with erase-before-write constraints and the endurance limits of NAND. Integrated into the database kernel, this logic doesn’t replace conventional flash-management goals but complements them by adding the timing guarantees that a real-time database depends on. That’s exactly why we moved to a transactional FTL (TFTL). By making flash management part of the transaction path, the database kernel stays in full control of media access and its latencies. It knows how much data will be written and when the flash will be touched, so garbage collection becomes a planned, bounded step rather than a background surprise. With the black box gone, wear leveling, block allocation, and page mapping fold into the same bounded and fully visible pipeline the transaction manager already drives. TFTL enables transactions directly on raw flash using a rotating page buffer with a small index instead of a full logical-to-physical map, making it practical in systems with limited RAM. The full TFTL algorithm is beyond this blog’s scope, but the basics are simple: on update, TFTL writes a new page copy to the active buffer position and updates the index so the logical address always refers to the latest version. This naturally spreads writes across blocks and keeps wear leveling balanced. On commit, the newest pages are marked; during recovery, TFTL walks back to the last committed state and restores the index. In effect, TFTL maintains full ACID guarantees while absorbing the essential flash-management duties.

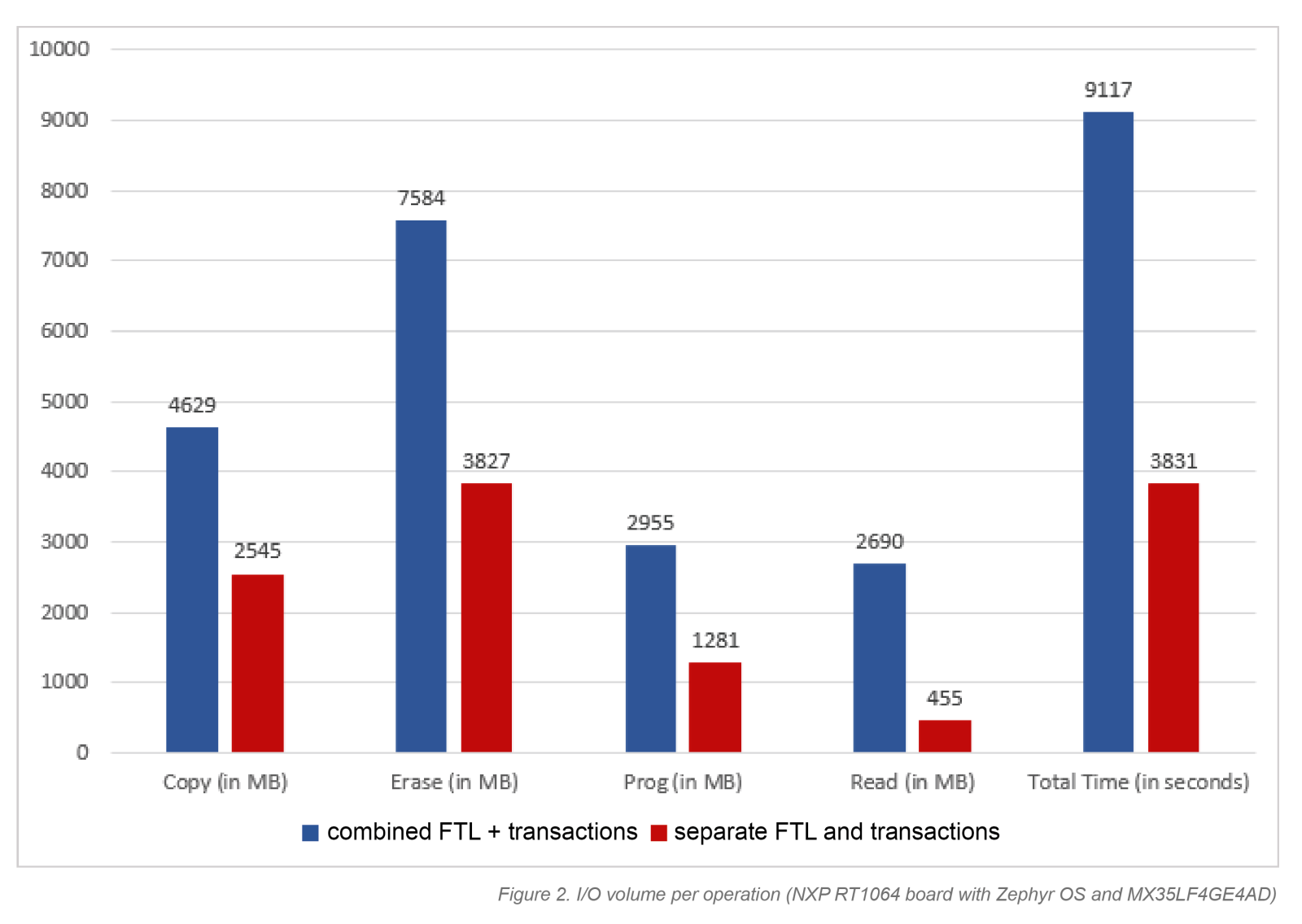

A welcome side effect of this integration is lower write amplification and improved wall-clock performance. With separate CoW and FTL mapping layers, every update gets translated twice. By merging them, that double mapping disappears, unnecessary copying is avoided, and wall-clock performance improves simply because the kernel is no longer working against an autonomous FTL underneath it (see Figure 2). And once the storage layer is finally predictable, the next challenge is making sure it still behaves that way when the system is actually doing its job.

A welcome side effect of this integration is lower write amplification and improved wall-clock performance. With separate CoW and FTL mapping layers, every update gets translated twice. By merging them, that double mapping disappears, unnecessary copying is avoided, and wall-clock performance improves simply because the kernel is no longer working against an autonomous FTL underneath it (see Figure 2). And once the storage layer is finally predictable, the next challenge is making sure it still behaves that way when the system is actually doing its job.

Why Real-Time Testing Is Never Simple

Our next installment will discuss a topic engineers rarely prioritize: QA and testing. In hard real-time embedded systems, QA isn’t just unavoidable, but it’s significantly more demanding than the kind of testing most software typically undergoes. You’ve got timing paths crossing hardware, drivers, RTOS services, and the database kernel itself, all nudging each other in ways that aren’t always obvious. It may seem that the only way to trust a hard real-time system is to test every piece under load, under fault conditions, and on actual hardware. There are standard QA techniques and established software frameworks that help with automation and structural coverage, but the wide variety of hardware platforms and RTOS environments makes it extremely costly and, honestly, pretty impractical to rely on real-hardware testing alone, even though hardware testing is still a necessary last step. We’ll also look into the practical side of QA for hard real-time database middleware: how to parameterize tests using specialized simulators, how to shape workloads to expose those tricky timing edges, and which repeatable procedures actually move the needle on confidence in the software.