Engineering Real-Time: Lessons Learned While Chasing Determinism Part 3

December 03, 2025

Story

In part 1 and part 2 of this series, we talked about two key real-time scheduling algorithms and how they fit into our real-time database goals. We also covered why scheduling alone isn’t enough, and how precise time measurement, predictable rollback, well-placed verification points, and a bit of real-world profiling are what actually make “on time” possible.

This installment moves to the next piece of the puzzle. Once timing and verification are in place, the focus shifts to what happens after an enforced abort and how the database kernel keeps logical and temporal consistency intact.

What “Stopping on Time” Really Takes

Database kernels get complex in a way that simpler software, like an RTOS scheduler never does. An RTOS scheduler is usually a small, tight piece of code that simply picks the next task and runs it. A database kernel is nothing like that — it’s layers of storage, indexes, caching, locking, transactions, all stacked together. Any kernel call can end up deep in that stack. And with timing verification points at every level, a deadline can expire anywhere — right at the top or buried inside some distant storage I/O call.

In a non-real-time database, error handling is mostly about keeping logical consistency intact: detect the error, unwind cleanly, leave the data in a safe state. A hard real-time kernel has to do all of that and also keep track of time at every step. The failure path, just like the commit path, is part of the timing model and must be predictable. The abort time has to be known precisely in advance, not approximated. When the timer says “stop,” the kernel must stop fast and in a controlled way. And the cleanup belongs at the top of the transaction manager layer, where the kernel actually knows how to restore things cleanly. Which brings us to the next question: how do you get back out of that deep call stack when a deadline expires? There are two fundamental approaches.

The first is the classic C approach: every function returns an error code, and the caller decides what to do next. On a deadline miss, a low-level routine returns a failure, its caller unwinds a bit of state and returns a failure, and that keeps going all the way up. It’s simple and familiar, but not great for hard real-time work — every layer has to know about the error, and the total unwind time depends on how many stack frames there are and how much cleanup each one decides to do. And because error handling has to appear in every execution branch of every function, the code gets more complicated and, in practice, less deterministic.

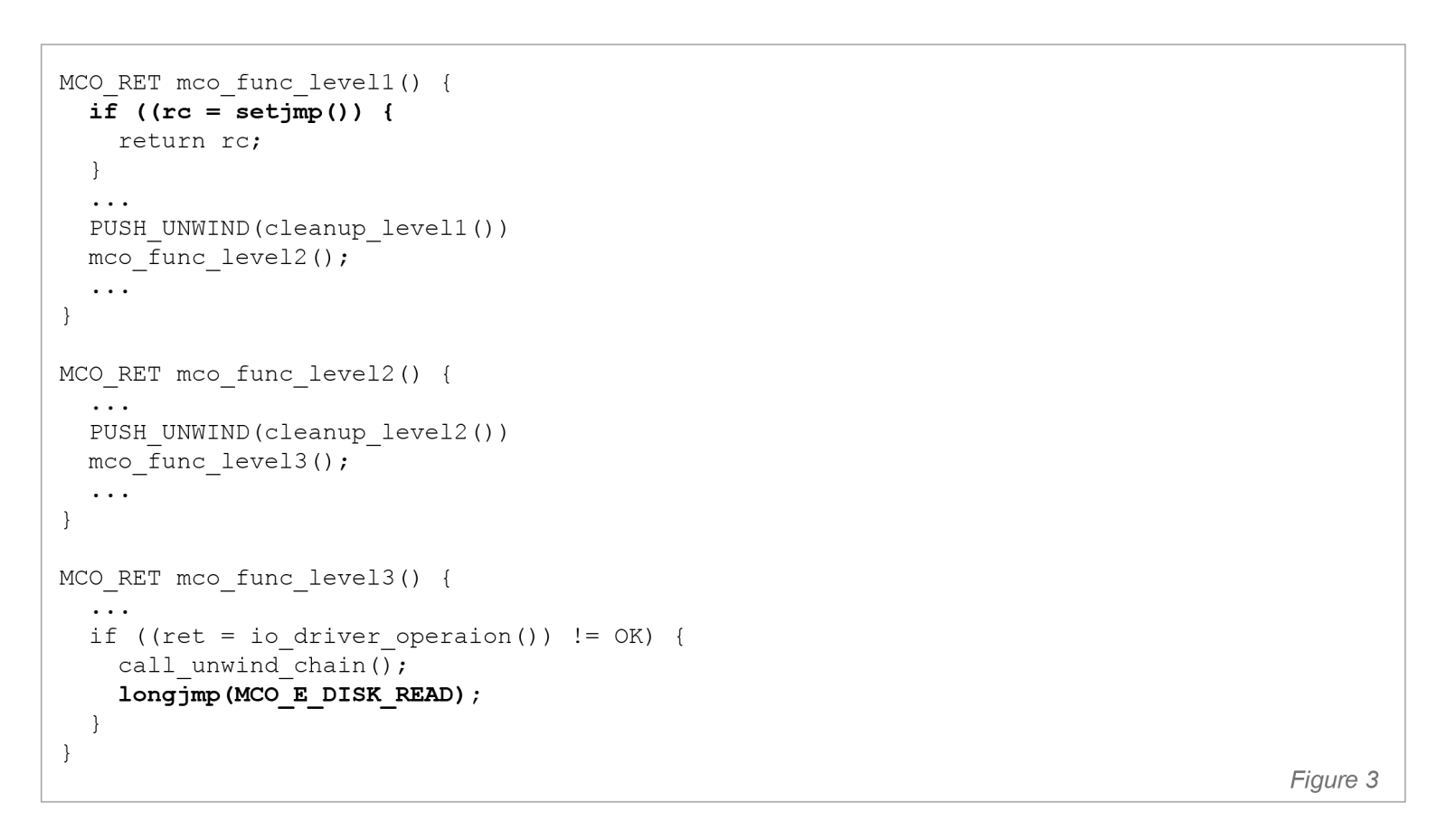

The second option is to skip the whole return chain and jump straight to a known recovery point. In C, this usually means using setjmp and longjmp — they are part of every standard C library. setjmp saves the calling environment (stack context, registers, program counter), and longjmp restores it later, effectively doing a non-local goto. The kernel sets up a top-level handler for the transaction (or for each API function exported from the kernel) and when a verification point decides the deadline is gone, it doesn’t crawl back through multiple layers of calls; it simply calls longjmp. Before that jump, a small, fixed set of cleanup callbacks run to release internal locks and restore any internal structures. Then control lands in the top-level handler, the one place that actually knows how to roll back the transaction safely.

Both approaches work, but only the second gives a hard real-time database kernel what it really needs: a short, fixed, centralized failure path with a well-defined cost. So let’s briefly walk through both alternatives using a pattern we rely on in the kernel, and look at the good parts of each and the places where they don’t quite hold up. It becomes even easier to see when you look at a real call stack.

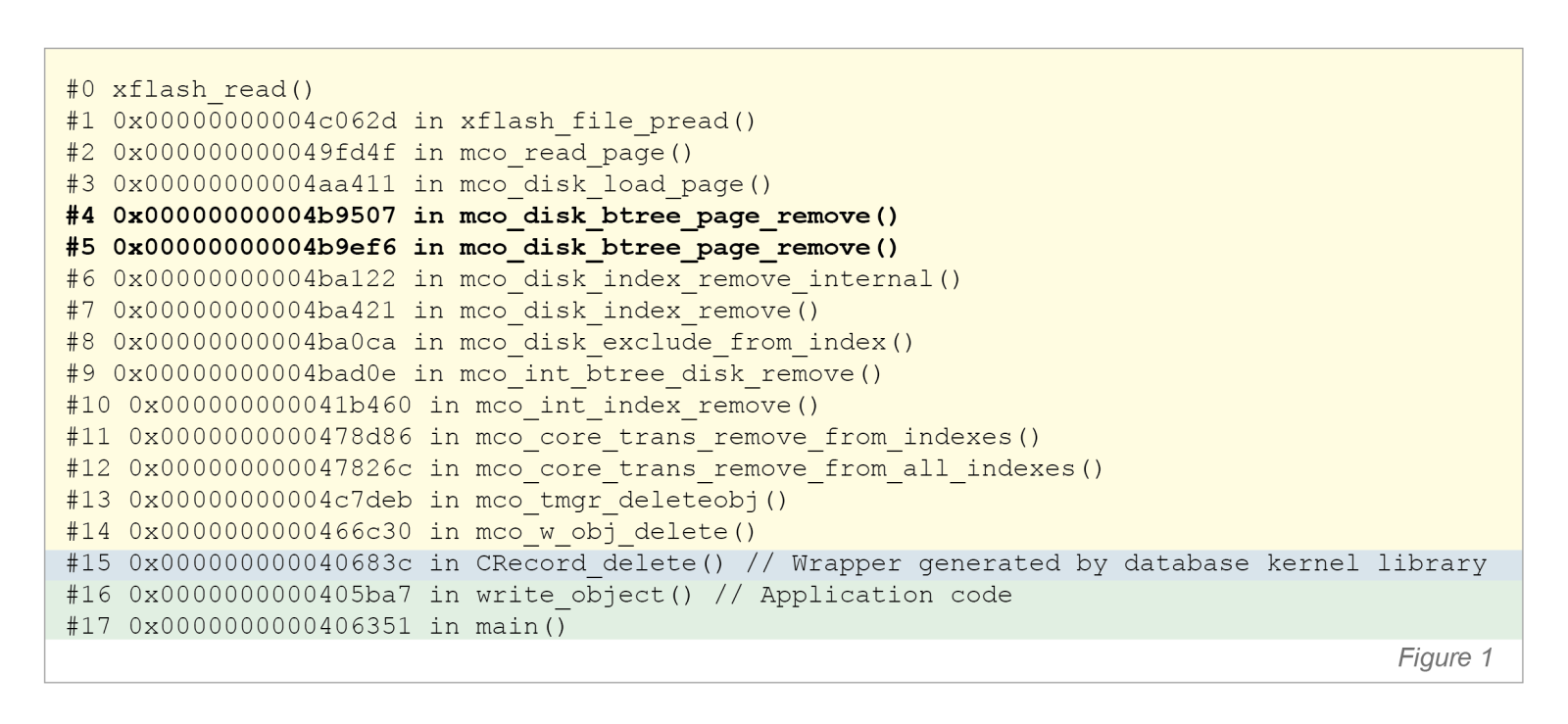

The actual call stack during object deletion may look like the one shown in Figure 1. In this case, execution happens to be inside the code that removes an object from a B-tree index.

The actual call stack during object deletion may look like the one shown in Figure 1. In this case, execution happens to be inside the code that removes an object from a B-tree index.

Because B-tree operations are typically implemented using recursive calls, the call depth can reach the height of the tree. In the example, those are frames #4 and #5 — calls to mco_disk_btree_page_remove(). xflash_read is a function from the low-level flash translation layer (FTL) subsystem that eventually invokes the media-driver routine responsible for reading a page from flash memory. Time-verification points are placed immediately before and after this call. If a signal to terminate the transaction arrives while execution is inside xflash_read, the kernel must unwind 15 nested stack frames, and do so quickly. At the same time, the actual cleanup logic — restoring internal structures — must execute in exactly one place, inside mco_disk_load_page(). All other intermediate modifications are undone later by the standard transaction-rollback mechanism, which runs after control is returned to the application.

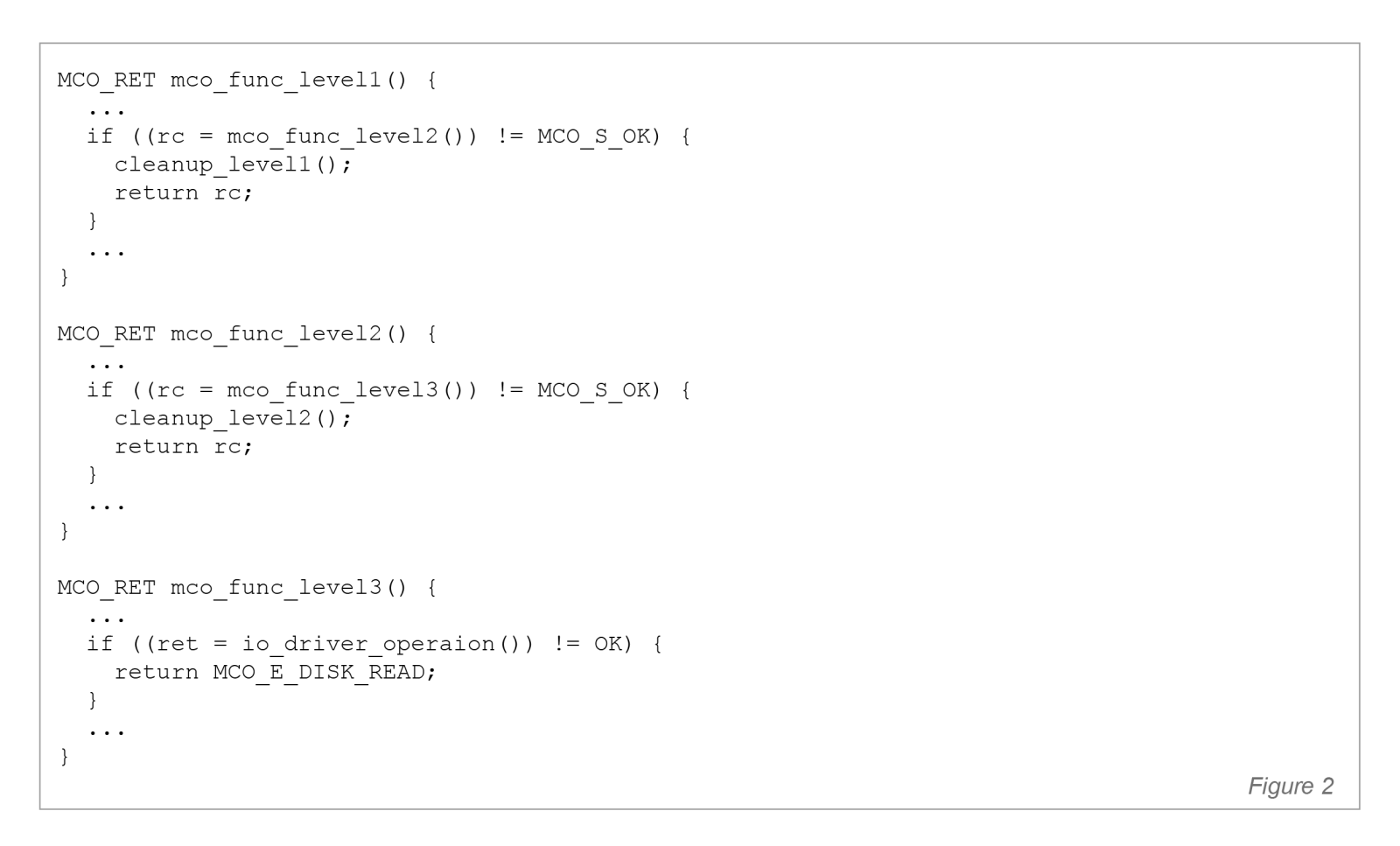

A return-based implementation logic is shown in Figure 2, and the setjmp/longjmp-based version in Figure 3. The difference is significant: walking back through 15 frames, one return at a time, is slow, unpredictable (because in any given instance it could 5, 10, 15 or any number of frames), and forces each frame to perform its own cleanup. With longjmp, the kernel can exit the entire call stack in a single, bounded step and perform cleanup once — at the top-level handler that has full context of the transaction.

A return-based implementation logic is shown in Figure 2, and the setjmp/longjmp-based version in Figure 3. The difference is significant: walking back through 15 frames, one return at a time, is slow, unpredictable (because in any given instance it could 5, 10, 15 or any number of frames), and forces each frame to perform its own cleanup. With longjmp, the kernel can exit the entire call stack in a single, bounded step and perform cleanup once — at the top-level handler that has full context of the transaction.

Certification Headaches vs. Engineering Reality

One downside of the setjmp/longjmp approach that’s worth calling out in hard real-time systems is certification. Authorities like FAA/EASA for aviation, ISO 26262 for automotive, and IEC 62304 for medical almost always ask about mechanisms like setjmp/longjmp. The issue isn’t how the code behaves at runtime — it’s the static picture they need to sign off on. A longjmp unwinds some number of stack frames, but that number isn’t known at compile time. That makes the control path harder to pin down in the kind of static reviews these standards rely on. From an engineering point of view, though, the approach has real value. It replaces a long chain of return-based unwinding with a single, bounded jump into a central handler. The failure path stays short, predictable, and easy to measure. And paired with the hardware profiling we talked about earlier, it gives us a practical way to enforce deadline aborts without spreading cleanup code across the kernel.

One downside of the setjmp/longjmp approach that’s worth calling out in hard real-time systems is certification. Authorities like FAA/EASA for aviation, ISO 26262 for automotive, and IEC 62304 for medical almost always ask about mechanisms like setjmp/longjmp. The issue isn’t how the code behaves at runtime — it’s the static picture they need to sign off on. A longjmp unwinds some number of stack frames, but that number isn’t known at compile time. That makes the control path harder to pin down in the kind of static reviews these standards rely on. From an engineering point of view, though, the approach has real value. It replaces a long chain of return-based unwinding with a single, bounded jump into a central handler. The failure path stays short, predictable, and easy to measure. And paired with the hardware profiling we talked about earlier, it gives us a practical way to enforce deadline aborts without spreading cleanup code across the kernel.

This is where certification starts to overlap with QA and testing — something we’ll get into in the next parts of the series. Certification reviewers want a clean, static picture. Real systems also need real evidence: timing traces, rollback runs, and repeatable tests that show the kernel behaves the way the model says it should. That gap between paperwork and what happens on real hardware is exactly where testing has to step in and close the gap.

Flash Memory: The Next Bottleneck

No discussion of modern real-time storage is complete without talking about flash. We’ve been treating storage media as if everything behaves like RAM — nice and predictable. It doesn’t. Flash brings its own set of headaches: program-erase cycles, wear-leveling, block remapping, and a bunch of controller quirks that can nudge real-time guarantees off course if you’re not paying close attention. So in Part 4, we’ll take a closer look at the messier side of flash and what a real-time database kernel has to do to keep timing predictable when the data actually needs to stick around (be persistent, versus volatile RAM).